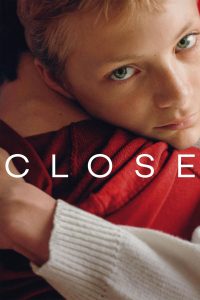

In the Belgian film «Close» from 2022 we see a school class of 13-year-olds “sharing” their thoughts and emotions about a sad incident. Everybody is allowed to speak. The socially intelligent teacher (whom I hold to be the most interesting adult figure in the film) does not put direct pressure on anybody to talk. And when she turns to the protagonist, who is one of the pupils, he says nothing, just that he is “fine”. This we know cannot be quite true, though, since he used to be a close friend of the deceased classmate.

Death

So, the death of a 13-year-old is the “incident” that has led to the sharing session. As I said, each participant is allowed to speak, but must not. So far, participation is voluntary. However, what is not “voluntary” is listening. This, in my opinion, is a much-underestimated aspect of “sharing”. If you want to enforce closeness in any given milieu, organise “sharing” regularly, and even sceptics will gradually be dragged into it. The film, however, coming out of our postmodern, mainstream culture, is all in favour of this. It is indiscriminately in favour of indiscriminate “sharing”.

The film is a low-key type of drama. It is mostly about people meeting, and later weeping, silently. The filming is soft and the colours are like watercolours. Only the sudden death of the protagonist’s classmate and best friend – by suicide – stands out as “dramatic”.

In my opinion the suicide, however, is not trustworthy. The incident is a crucial part of the story told, but does not, in my opinion, appear as explicable from what we see. What we see, is some classmates teasing the two friends for appearing like a “couple” – that would be a homosexual couple. Part of the mainstream culture is to see homosexuality as just as plausible as heterosexuality, and another part is sexualisation of childhood. But the teasing is just as low-key as everything else in the film. From what we see, there is little reason for the two friends to be annoyed.

But you CAN IMAGINE that the motives of the classmate are eviler that what we see in the film. In real life they might be so, and the alert presence of adult authority would then be a good idea.

Distance

Returning to the film, the protagonist now starts holding some distance to his best friend. We see him refusing to let the best friend rest his head on his stomach when they are lying in the grass. And then there is the bed. At the age of 13, the two friends, when visiting each other and staying overnight, tend to sleep not only in the same room, but in the same bed. I find this odd. Normally a 13-year-old would not even have a bed broad enough for two. I recall, 13 was exactly the age from which my daughter was no longer permitted to sleep in MY bed (when my wife was on travel). Growing up to be an independent person takes place in steps. Learning and enjoying the opposite of closeness is part of growing up.

However, if the adults don’t help, the children will seek the necessary distance to other persons anyway. As we know, they step-wise seek independence from their caretakers. They join their peers in collective opposition. But children are not only a new, forthcoming generation, they are individuals also seeking some distinction among themselves. How to combine individual distinction with contact and closeness, is part of growing up and later maturing.

A primitive way of bringing some distance, is quarreling. 13-year-olds typically do that – sometimes quarreling exactly with their best friend.

In the film “Close”, however, anything similar to quarreling between the two best friends appears like a calamity – quickly leading to the real calamity of one of them killing himself.

We see the survivor of the two, Rémi, one day refusing to share bed. We also see him bicycling to school alone, not meeting his friend Léo on the way as usual. Léo, instead of with some sadness accepting his friend’s move, which I think would be the normal reaction, asks the question “why” when he meets Rémi at school. He behaves as if Rémi had broken a marriage (in the old days). Rémi then evasively says that he woke up too early and had breakfast too early. Léo, however, again, instead of with some sadness accepting this evasive distance-keeping, can’t BELIEVE that his best friend is LYING to him. Soon after he kills himself.

Ridiculous

I am sorry to say that I find this to be almost ridiculous. But when seeing the film, the “ridiculous suicide” – which we hear of, we don’t actually see it – is baked into the overall soft, “watercolour” concept seducing the audience to go along with it.

Does the film have a message? I will say yes. If you don’t reflect carefully over the film, but go along with it, the message is this: DON’T YOU EVER SAY A NEGATIVE OR CRITICAL WORD ABOUT ANYBODY, and in particular NOT ON THEIR BEHAVIOUR IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF SEXUALITY. And most important: DON’T EVER SAY A NEGATIVE WORD ABOUT HOMOSEXUALITY! If you do, you may be complacent of somebody’s death.

In real life, however, I believe people are still more resilient. But we are building a culture in which we are told not to be. Children should learn from their parents, but in the film “Close” the parents are not very different from the children, just older. The parents of the two best friends deal with their children on equal footing. The only adult with some authority in the film is the teacher. This is also a part of postmodern culture. Authority comes with formal position on behalf of society (or even the state) rather than being based on love and life-experience.

Do I then mean that you should never “share” your sorrow and cry before others? No, I don’t. My point is that you should be selective. To cry before others is to surrender. Consider carefully to whom you will surrender.

Aggression

In the film the only “aggression” we see, beyond the “self-aggression” inflicted by the suicidal child, is the children relatively softly teasing the two best friends. In real life, however, it is not always soft among children. As I said above, what we need then is alert adult presence.

Should the adults then be aggressive against the aggression of the children? It depends how you define “aggressive”. If you define it as aimed at extinction, the answer is no. However, if you define it as correcting someone’s destructive behaviour, I would say yes – if necessary, angrily – being it towards a child or towards an adult. To see the difference between anger for extinction and anger for correction, you need to see the world with some clarity – not in soft watercolours.

However, you will then, as a “bonus”, be able to see the many erroneous ways human aggression takes today, because it is blocked in normal, everyday life. But those are different questions that shall not be addressed here.

[…] Du er hermed advart mot en film som forherliger det feminine og forviser det mannlige til en innhegning på 30 x 60 meter. Flere advarsler mot filmen – den er et uttrykk for den postmoderne kultur – kan du lese (på engelsk) i min kunst-blogg. […]