The film “Cider House Rules” (1999) demonstrates the postmodern “catechism”

A young man (whose name I have forgotten, I shall call him X) from an orphanage “asks” the tall and strong chief of the labour team if he sleeps with his own daughter. Of course, this is an accusation. Earlier we have seen the chief persuading his employees with his muscles, sometimes underpinned by a knife.

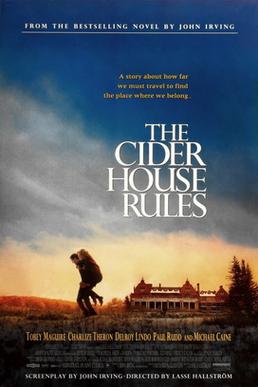

This is the dramatic climax of the film “The Cider House Rules” (1999, based on a novel by John Irvin, 1985) – dramatic if you believe in the film. I don’t believe in it, and I’ll come back to that. But let me first tell you what happens.

A story?

The film plays in the nineteen-forties in England. We are in an orphanage and meet children and personnel. Not far from the orphanage, there is a farm where we find a crew of fruit pickers in the season. The answer to the above question about incest is yes. The culprit (the chief) does not confess, but surprisingly, following the accusation, we see the brutal chief sink into a (well-deserved) moral depression. He ultimately dies from wounds that his abused, but soon emancipated, daughter inflicts upon him. His last wish is that those who know, do not tell the truth about his death.

I will not exclude that a person can carry such strong moral authority, that even an incestuous muscle man with a knife will succumb. However, in the case of “Cider Rules,“ I cannot see how the young man X would be such a person. In the orphanage, he grew up under the auspices of a friendly, but weak doctor. The doctor is the head of the orphanage and also runs a clinic by which he carries out abortions – illegal at the time. The young man X serves as an assistant. The doctor’s weakness becomes manifest when his assistant and “foster son” decides to leave the house to enter the bigger world. The doctor is emotionally unable to let him go. For sleep, the doctor depends on inhaling a few drops of ether every night, a habit that ultimately kills him.

However, from this doctor, the young man has learned how to perform an abortion. This comes in handy when he shall relive the unfortunate daughter of a tragic pregnancy deriving from the father. But psychic or moral strength X has certainly not learned from the doctor. His ability to make a brutal-type strong man quiver under his questioning, remains inexplicable … unless the team chief should be a former Sunday school pupil? – who somewhere deep down has kept his moral light burning? Not so, as far as the film lets us know. Like the moral authority of the young man, the sudden disappearance of the chief’s brutal-type strength remains inexplicable.

I believe we shall have to seek outside the film for explanations of what happens in it. But let me first refer yet another couple of things happening. We meet a young, engaged couple, and the woman, named Candy, is pregnant. The woman and her prospective husband, who is a military officer, come to the clinic at the orphanage and the woman has an abortion. Later, we see our young man X have his first romance with this woman. The romantic encounter (an “affair”) occurs spontaneously after the woman’s fiancé has voluntarily gone to fight in the war on the other side of the world. Later we hear that the officer suffers a loss of health – not wounded in combat, but paralysed by an infection contracted in the jungle.

The postmodern “catechism”

How to explain what happens in the film? I will suggest that the film has nothing to do with reality. Rather it should be understood as a demonstration of what we can call the postmodern catechism.

Anybody interested will have noticed that the postmodern belief system includes 3-4 basic preferences, or moral distinctions. They go as follows: 1) female is better than male 2) everything is better than heterosexuality 3) non-white is better than white, and then there is 4) something about class. The fourth preference is not as clear-cut as the other three. However, “low” is better than “upper” is a practical simplification.

But what does “better than” mean? It is basically about victimhood. The above-mentioned moral preferences are basically negative – it is not about female, black, etc. being good, it is about male, white, etc. being bad. “Better” means that the better category has been more of a victim to evil forces throughout history. Today they are entitled to restoration and compensation, whereas the opposite category shall feel guilt and shame.

Certainly, the film demonstrates preference 1. There are four male characters: The weak doctor, the ugly team chief, the unlucky military officer and then there is the young man X. The young man X also appears rather weak, in my opinion, or at least he shows no personal strength. The young man X does not need personal strength in the postmodern world. He is simply on the right side and automatically wins.

How about the women? We see only two women clearly: the abused daughter and Candy. The abused daughter is strong enough to kill her father, a performance that we do not see, but are simply told. I cannot see Candy showing any strength eitehr, but I guess it is with her like with the young man X: she is on the right side. There are two ways in which you can be on the right side: 1) by birth, and this is the noble way, and 2) by taking a stance. The latter applies to the young man X. He takes a stance for the abused daughter and gets to the right side of the sex divide. Candy is born on the right side of the sex divide, however – being white – on the wrong side of the racial divide.

Here is the underlying theme of the film. I will suggest the film is about pushing the priority of preference 1 above preference 3 in the postmodern belief system. The “discussion” about preference 1 versus preference 3 has been going on for some time. Throughout the 20th century, preference 3 has mostly been stronger than 1. A country, for example, has tended to defend a man of its own against a woman of another country (say, in a child custody case).

Like boxing

Let us see if we can sort out what happens in the film along the two divides constituted by postmodernism’s preference 1 and preference 3. We try counting points like in boxing. Since we are not talking about people with a real character anyway, what wins is features, not persons.

The most conspicuous thing happening is the incest committed. The incest shows the moral inferiority of a man. In “Cider Rules” the whole fruit-picking team is black, so racially the incest is neutral. I guess the second most conspicuous event is the killing. Again, this is racially neutral, but regarding sex, it shows the superiority of rightful female anger against male physical strength. So far, we have two events pushing preference 1, and regarding preference 3, there is a draw.

We should also look into the confrontation between the young man X and the black chief. We see the black chief succumb to the investigative question of the young man X, who is white. Regarding sex the immediate outcome of the confrontation is neutral, being between two men, but secondary it is about siding with female against male. Let us count half a point in support of preference 1 for that. Regarding race, the immediate outcome is white wins over black, but secondary it is neutral as siding with the black daughter wins against the black father. We count one full point against preference 3.

In sum, we now have 2,5 points in support of preference 1 (sex), and 1 point against preference 3 (race) of the catechism. But is postmodern fiction able to “sacrifice” one preference against another – even taking a situational defeat for a preference, in this case, preference 3?

To this question, I will answer: of course! Postmodernism is not much concerned about consistency. Consistency is part of traditional justice – the postmodern take on morality is different. It is more about association and feelings (and ultimately power rules, I will come back to that).

Let us finish our counting by looking at Candy. She is born with the right sex only, and she does not take much of a stand. She is white and she is also the employer of the fruit picking crew. She is by birth on the wrong side of the racial divide as well as of the class divide. If sex is the most important preference, we could expect her to succeed anyway. But in the film her outcome is fairly bleak – she is bound to her fiancé who is now in a wheelchair. I guess we can conclude that being on the right sex can outweigh one other preference, but perhaps not two.

Reality

After I had seen “Cider Rules”, I could not remember any character’s names, except “Candy”. All other names I had forgotten. I think this underlines the impersonal character of the story. Life is about following a script. Follow the postmodern script, and you will be on the right side.

You may agree or disagree regarding my understanding of postmodernism. In any case, I will encourage you to look closely at the characters in contemporary films you see. Compare them to real people you know. Sharpen your sense of what a real human is like. My analyses of the film rest on my rejection of the characters we are shown as not trustworthy. If you disagree with my judgement, I shall respect that. But I would like to hear your description and understanding of the characters.

The greatest danger of postmodernism, in my opinion, is not that it seizes the larger part of the population and pushes the rest of us to the margins. The greatest danger is that we all unlearn what a human being is – socially and morally speaking. The figures we saw in the film “Cider Rules “, and can see in other films, can become “real” if we turn to living by script.

Schreibe einen Kommentar